Correctional Officer Recruitment & Retention Efforts

A StudyReport Summary

Conclusion

Background

Alabama has historically struggled to hire and retain correctional officers. To address this, the Alabama Department of Corrections (ADOC) established a recruitment and retention program in 2019 that provided bonuses up to $7,500. The program expired at the end of 2022, but eligible officers can still earn bonuses through 2025. Additionally, ADOC raised correctional officer salaries by 5%, created a correctional officer senior classification, and increased starting pay to over $50,000 annually in 2023. By FY23’s end, ADOC had paid nearly $10 million in bonuses, with 660 employees still eligible for $1.8 million more.

Key Findings

- Correctional officers are less likely to resign after implementation of the compensation and classification changes.

- ADOC has avoided between $7.9 million and $10 million in voluntary turnover cost since FY19.

- ADOC’s correctional officer turnover rates are better than other states.

- ADOC’s correctional officer turnover is consistently higher than other state law enforcement positions.

- Compensation changes have not improved hiring during the review period.

EFFECTIVENESS OF CORRECTIONAL OFFICER RECRUITMENT AND RETENTION EFFORTS

Historically, Alabama, along with many other states, have struggled to hire and retain prison security staff – specifically correctional officers. In 2018, the Alabama Department of Corrections (ADOC) was granted authority to establish a pilot program to aid in the recruitment and retention of correctional officers. [ii] A year later, the program was codified in state law, authorizing employees in the correctional officer classification series one-time bonus payments with the opportunity to earn up to $7,500 through promotions. [iii] The program expired on December 31, 2022, for an officer to be eligible for bonuses under the program. Any eligible officer who did not receive the full amount of bonuses prior to December 31, 2022, can still earn retention bonuses through December 31, 2025.

Braggs V. Dunn

Over a decade ago, the state of Alabama was sued with the plaintiffs alleging that the ADOC provided inadequate medical and mental health services. Three years into the Braggs v. Dunn case, the court found “that the State of Alabama provides inadequate mental-health care” due largely to chronic understaffing. Four years later in 2021, the court issued a new mandate for the department to increase security staffing by nearly 75%. [i]

The act also granted a one-time, two-step salary increase for all employees in the correctional officer classification series, effectively raising correctional officer salaries 5% across the board. During this same time frame, the salary ranges for these classifications were increased, resulting in a higher minimum and maximum salary for each classification. In addition to the compensation changes, the Alabama State Personnel Department, working with ADOC, also created a new Correctional Officer, Senior classification. [1] With this new classification, correctional officers were provided an additional promotional opportunity. This new classification created another opportunity for salary increases for existing correctional officers beginning with provisional appointments on February 1, 2020. [iv] As with any merit system classification, an employee entering the Correctional Officer, Senior classification would be eligible for an initial 5% (two-step) salary increase and an additional 5% salary increase at the end of an initial six-month probationary period.

In March of 2023, the salary ranges and starting pay were again raised for correctional officers. [v] The most significant of these changes was increasing the starting pay of Correctional Officer Trainees to over $50,000 a year (previously $33,381). Combined, the changes to compensation and classification represent substantial monetary incentives to become and remain employed with the Alabama Department of Corrections.

At the close of FY23, ADOC had paid $9,746,568 in recruitment and retention bonuses with roughly 660 employees still eligible to receive up to $1,800,000 in bonuses.

Purpose and Scope of the Evaluation

This evaluation sought to examine the effectiveness of the bonuses by whether they impacted the recruitment and retention of correctional officers for the Department of Corrections. Due to the compact timing of all the compensation changes, it is not possible to delineate the impacts of just the Recruitment and Retention Bonus Program from the other compensation changes. As such, this evaluation seeks to determine the impact of the totality of compensation changes. Because the act creating the bonus program specifically states recruitment and retention was its purpose, the evaluation analyzed both turnover and hiring.

For the purposes of determining that impact, employment records from the State Personnel Department were obtained and analyzed from FY15 through FY23. A date of May 29, 2019, was selected to differentiate pre- and post- program changes because it represents the earliest point as which changes to compensation could be officially communicated. The methodology created a pre-program length of 56 months and a post-program length of 52 months.

Statistical analysis was performed analyzing differences in hiring, retention, and turnover between pre-program and post-program data. A turnover cost model was built to analyze annual turnover cost and potential avoided cost from the program. See Data and Methodologies for more information and details of the analysis.

Summary of Findings

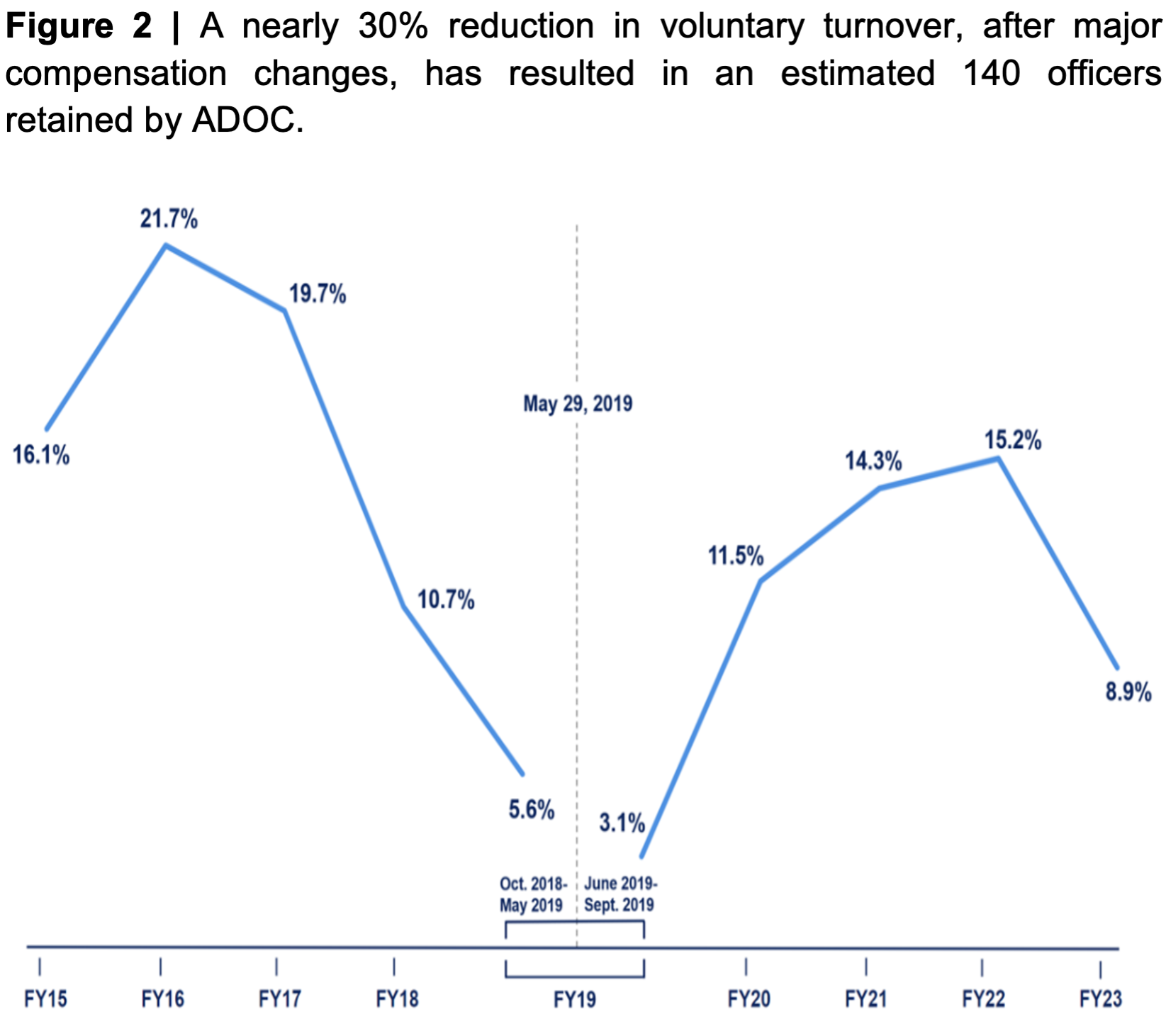

Correctional officers are less likely to resign after implementation of the compensation and classification changes. Correctional officer resignations declined by an annual average of over 4% during the post-program period. Voluntary turnover also decreased for Correctional Officer Trainees by over 5%. The statistically significant effect for correctional officers resulted in an estimated 140 officers retained, nearly 17% of the current correctional officers.

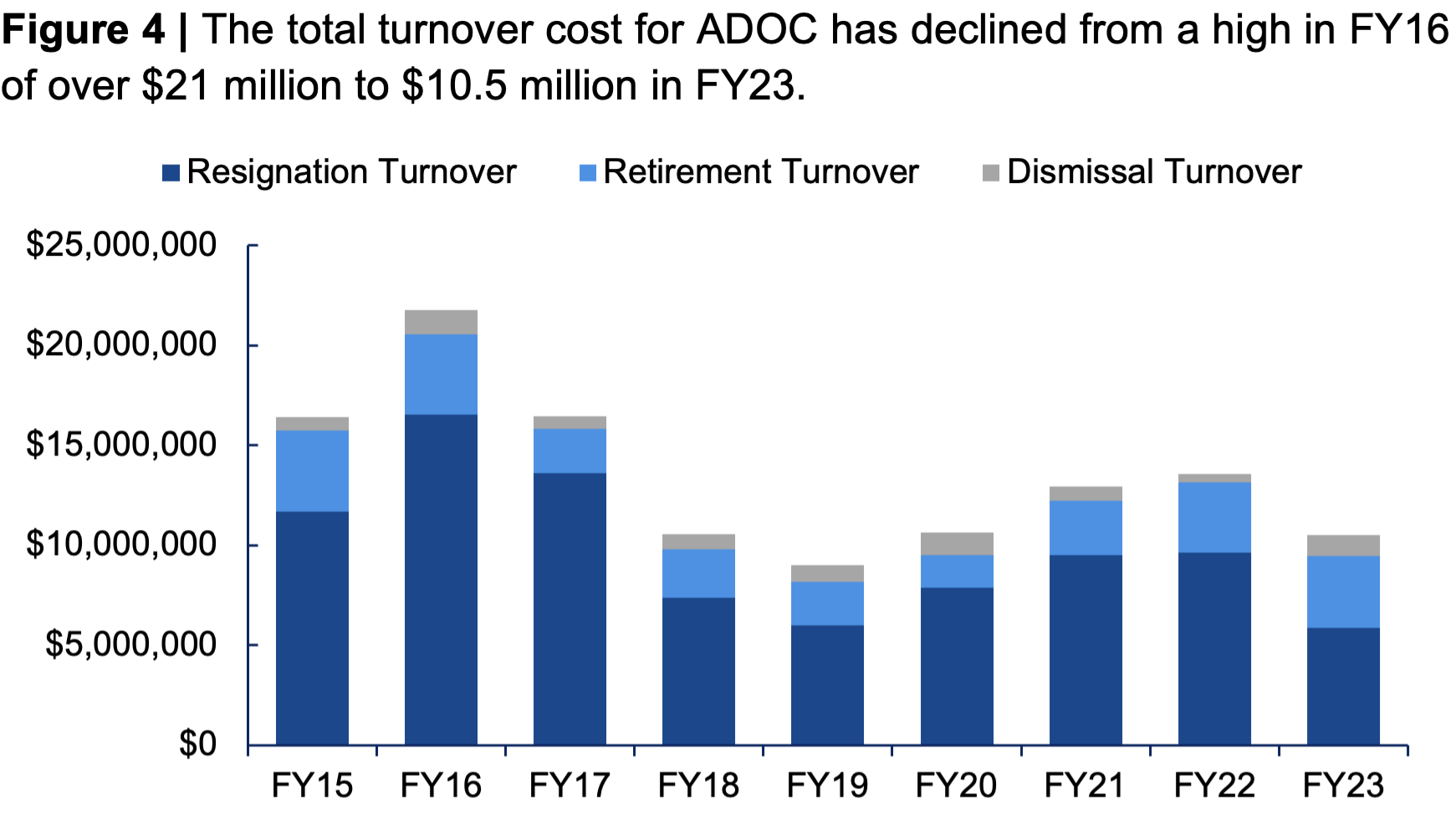

Correctional officer turnover costs ADOC over $11,000,000 a year. The time it takes to hire a new officer, train them, and fill a vacant position is nearly 17 weeks on average. The expense of covering a vacant position with overtime coupled with training cost drives turnover costs for the department.

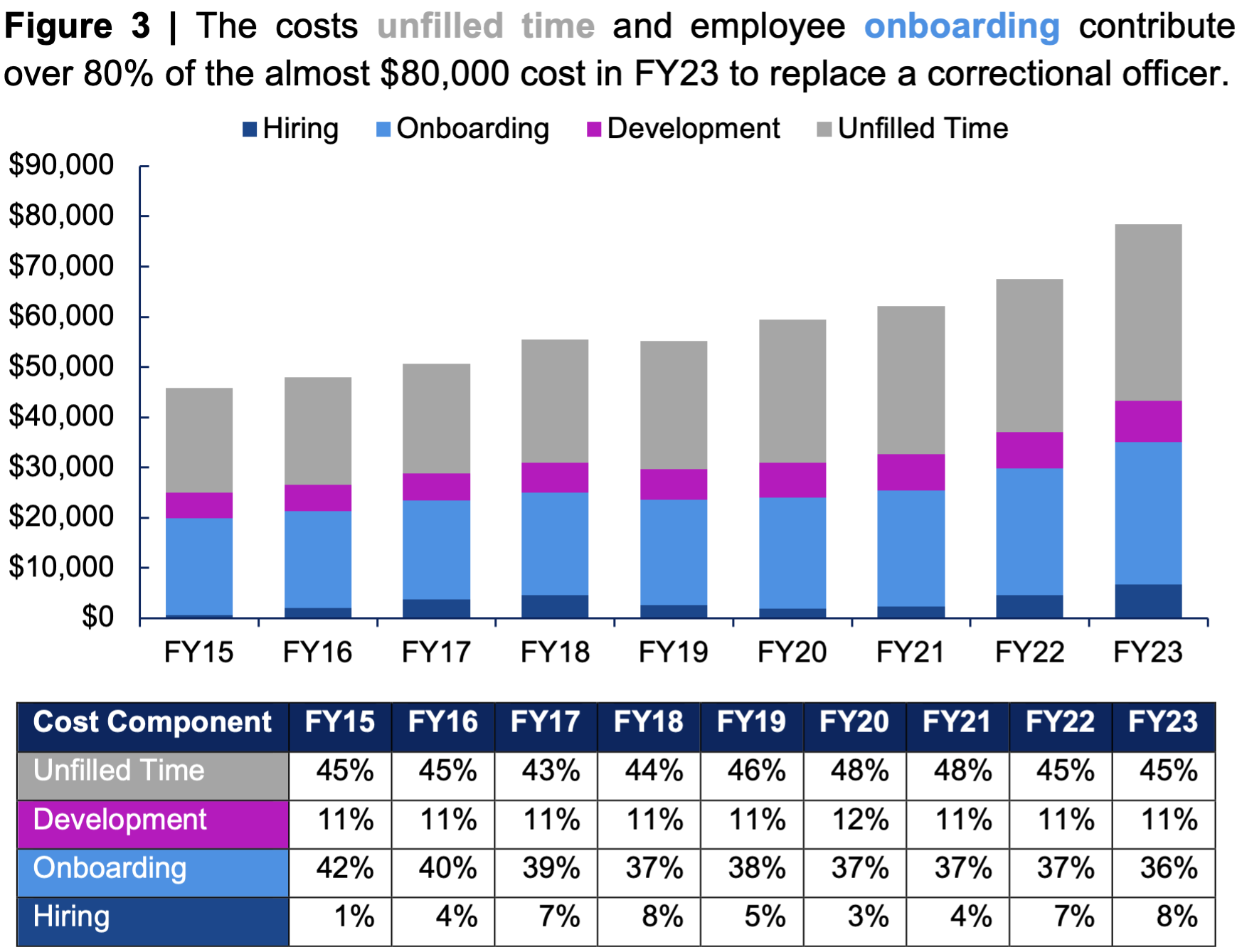

ADOC has avoided between $7.9 million and $10 million in voluntary turnover cost during the post-program period. With annual turnover cost averaging over $60,000 per separation, ADOC has avoided significant costs from reduced resignations. However, the avoided cost to date only covers part of the full cost of compensation changes.

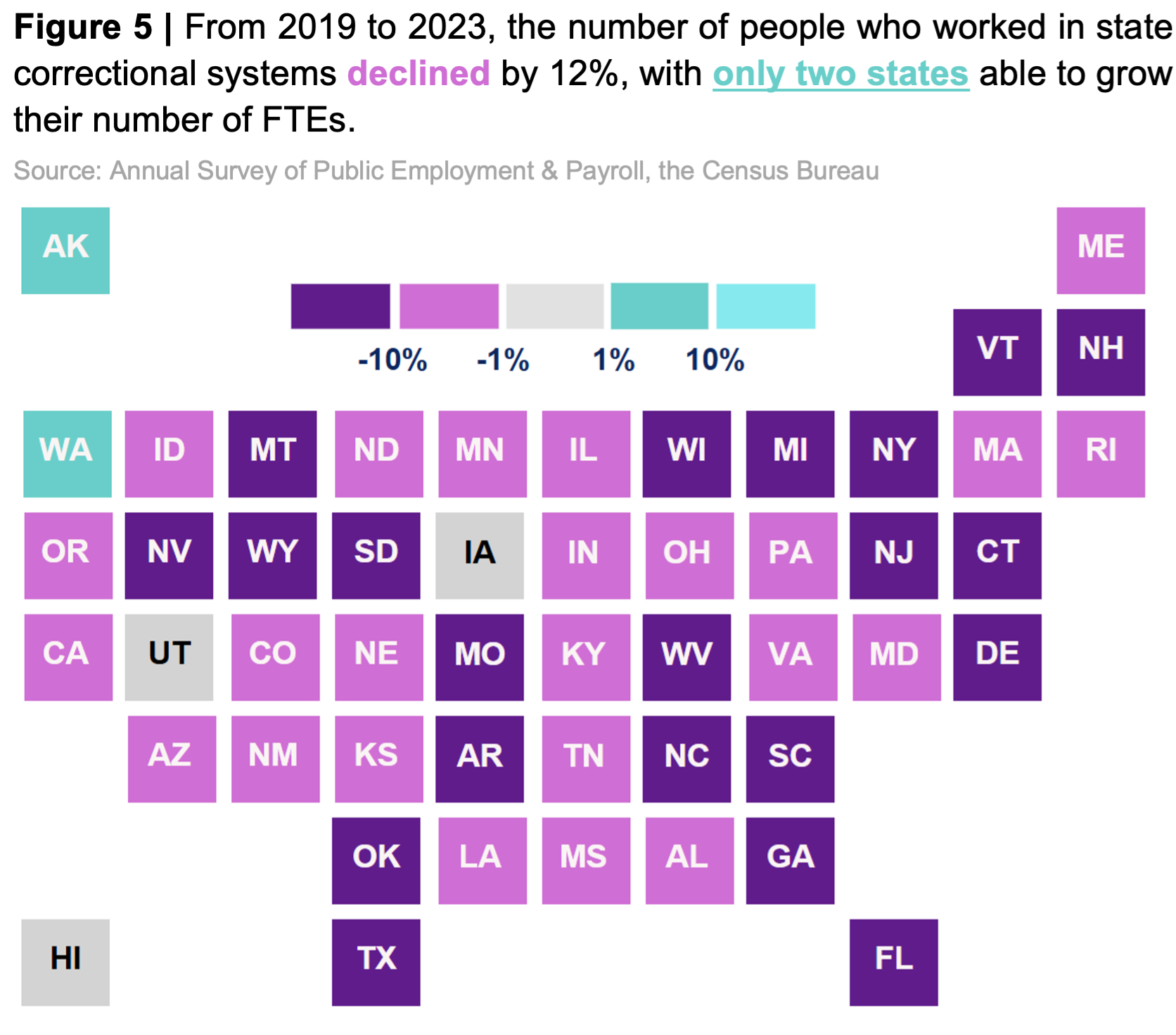

ADOC’s correctional officer turnover rates are better than other states. Nearly all states (45) have experienced a decline in correctional officer staffing over the last several years. While Alabama is among the states dealing with the decline, Alabama consistently has a lower correctional officer turnover rate than surrounding states. Additionally, several states are attempting to address their staffing issues with bonuses and other compensation changes similar to Alabama.

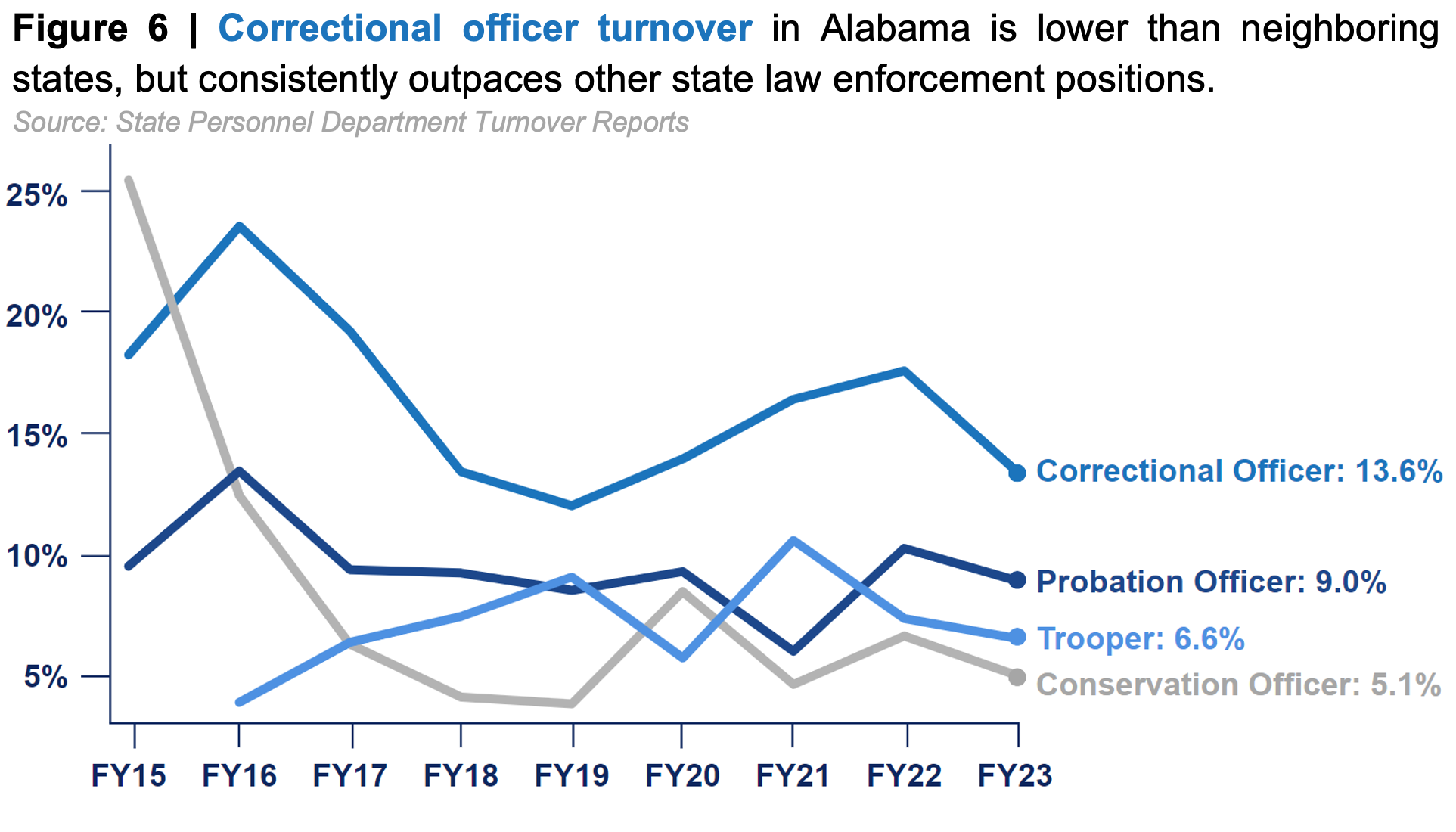

ADOC’s correctional officer turnover is consistently higher than other state law enforcement positions. Correctional officer turnover is higher than that of state troopers, probation and parole officers, and conservation officers even though pay and benefits are largely comparable.

Compensation changes have not improved hiring during the review period. Correctional officer hiring rates declined for most of the post-program period. The inability to hire officers more than offsets the improved turnover rates, resulting in more vacancies within the correctional officer position. There is some evidence of improved hiring rates for FY23 which has continued into FY24 – beyond the scope of this evaluation.

Correctional Security Guards have helped balance staffing rates. The hiring of over 1,300 Correctional Security Guards since FY19 has kept overall staffing rates level. These positions free up correctional officers for posts that require certified law enforcement.

Detailed Findings

1.0 Turnover of Correctional Officers

Correctional officers are less likely to resign after implementation of the compensation and classification changes. [2] During the post-program study period, correctional officers were 28% less likely to resign from the department than they were during the pre-program period.

Correctional officer voluntary turnover [3] – separations based on resignations – averaged 14.78% annually during the pre-program period. After several compensation changes were made, the voluntary turnover rate decreased to an annual average of 10.6% during the post-program period. See Figure 2.

Cause of Turnover

While pay appears to be an important factor in retaining officers, it is likely not the only reason. ACES conducted analysis on other variables to determine if this significance could be explained by other population or economic changes. None of those variables proved to be closely associated with hiring or retention of correctional officers. ACES also conducted a survey of bonus-eligible officers to determine what factors impacted their current and future employment with the department, but a low response rate limited the usefulness of the survey results. Finally, it should be acknowledged that a new Commissioner was appointed on January 1, 2022. The qualitative and structural changes that inevitably comes with new leadership cannot be measured. The fact that this appointment occurred more than halfway into the post-program period limits some of the impact on the results of this analysis.

It should also be noted that voluntary turnover for the Correctional Officer Trainees is down an annualized average over 5% during the post-program period, although the difference was not measured to be statistically significant. There has also been a slight increase in resignations among supervisors. [4] See Table 1.

Correctional officer turnover costs ADOC over $11,000,000 a year on average. Turnover is costly. When an employee leaves, the organization incurs direct costs such as hiring and recruitment expenses, onboarding and developing new hires, and separation payouts. Additionally, there are indirect costs like productivity loss from unfilled positions during the transition period and the time it takes for new employees to reach full productivity. Figure 3 shows the breakdown of these turnover costs for ADOC from FY15 to FY23.

Between FY19 and FY23, the individual cost of correctional officer turnover rose from $55,176 to $78,402 – a weighted average cost of $64,635. During that same period, ADOC averaged 177 correctional officer separations per year for all reasons – retirements, dismissals, and resignations – which is 40% fewer separations per year than in the pre-program period. Despite an individual turnover cost that is 71% higher in FY23 than it was in FY15, the total annual correctional officer turnover cost for ADOC has declined. See Figure 4.

ADOC has avoided between $7.9 million and $10 million in voluntary turnover cost during the post-program period. The cost avoidance is attributable to the reduced number of resignations among correctional officers since the beginning of compensation changes (140). While this amount does not cover the full cost to the department of the total compensation changes, it does defray the cost of those changes. It should also be noted that improved turnover rates will help the department make progress in reaching the staffing goals set by the federal court in Braggs v. Dunn.

ADOC’s correctional officer turnover rates are better than other states. A review of correctional officer turnover rates among surrounding states shows that Alabama’s turnover rate is much lower. Even when including the higher volatility positions like correctional officer trainee and security guard, ADOC’s turnover rate never exceeds 30% a year. In contrast, recent correctional officer turnover rates in Florida, Georgia, Mississippi, Tennessee, and South Carolina are all above 35%. [vi] In some instances, rates have even been reported above 100%.

These high turnover rates among other states have compelled policymakers to make or suggest compensation changes like those taken by Alabama. Florida has introduced salary increases and recruitment and retention bonuses in the last year. Georgia has raised the salary in back-to-back years for correctional officers, and Mississippi increased officer salaries by 10% in 2022. Non-neighboring states have also made significant compensation adjustments in recent years. In general, most states are dealing with a decline in correctional officers. See Figure 5. These trends are forcing states to address the issue, primarily through increased compensation.

While ADOC’s correctional officer turnover may be lower than other states, it is consistently higher than other Alabama state law enforcement positions. Surveys conducted by the American Correctional Association regularly cite inadequate pay as a top reason for correctional officer turnover. Other studies indicate that this is particularly a factor when the pay is low relative to other law enforcement positions. The recent compensation changes for correctional officers addressed both of those oft-cited factors. Correctional officer turnover is consistently more than 30% higher than state law enforcement officers with the Alabama Law Enforcement Agency, the Alabama Bureau of Pardons and Paroles, and the Alabama Department of Conservation and Natural Resources, even though these positions offer similarly competitive pay and benefits. See Figure 6.

This indicates that while pay is an important factor in recruiting and retaining correctional officers, it is not the only factor. The other top factors that are consistently cited in studies and surveys are:

- High Stress and Dangerous Work Environment: The stress and danger associated with the job can lead to burnout and high turnover rates.

- Supervisors: Quality supervisors can mitigate many problems an employee might have. In contrast, a lack of trust, perception of unfair treatment, or favoritism among supervisors can lead to low morale and high turnover.

- Staffing Shortages and Overwork: In many cases, correctional facilities are understaffed, leading to mandatory overtime for existing officers. This can contribute to fatigue and dissatisfaction among staff, further exacerbating retention issues.

- High Rates of Injury and Illness: Correctional officers are at risk of sustaining injuries or developing health problems due to the nature of their work, including physical altercations with inmates and exposure to infectious diseases. Concerns about workplace safety can deter potential candidates and contribute to retention challenges.

- Limited Resources and Support: Some correctional facilities may lack adequate resources, training, and support systems for their officers, which can impact job satisfaction and retention rates. Without sufficient support, officers may feel overwhelmed and disillusioned with their roles.

2.0 Hiring of Correctional Officers

Compensation changes have not improved hiring during the review period. During the pre-program years, ADOC averaged 242 hires into the correctional officer classification series. That average has dropped 50% to 123 hires per year in the post-program period. See Figure 7. The difficulty to hire new correctional officers over the last nine years has led to a 55% decline in correctional officer staff. Despite better overall retention of correctional officers and trainees, vacancy rates have increased. This hiring trend appears to be turning around with recent hiring on the rise.

Hiring on the Rise

In FY23, ADOC hired 201 new employees into the correctional officer classification series. This represents the largest number of new hires for the department since before the COVID-19 pandemic. This increase in hires was also accompanied by the lowest annual turnover rate since FY19 – the second lowest rate over the last nine years.

Correctional Security Guards have helped balance staffing rates. In FY19, ADOC, working with the State Personnel Department, created the correctional security guard classification to increase the number of security personnel employed. This new classification does not require the full, ten-week Alabama Peace Officers Standards and Training Commission (APOSTC) course and therefore, represents an easier point of entry. At the close of FY23, ADOC had hired 1,334 Correctional Security Guards. The overall effect has balanced staffing rates for the department. See Figure 8.

In theory, the correctional security guard position should also create an internal pool of candidates to recruit into correctional officer positions. Once the employees become familiar with employment in the department and working inside a state prison, the fear of the unknown should be assuaged to some degree. Familiarity, combined with higher income opportunities, should lead to promotions. However, of all the individuals that started employment with ADOC as a correctional security guard, only 3% obtained correctional officer status. One explanation for the low conversion rate is the inability of Correctional Security Guards to meet the necessary physical and background requirements to achieve APOSTC certification.

CONCLUSION

Correctional officer staffing rates continued to decline while separations outpace hiring for nearly a decade. While recent compensation changes have reduced voluntary turnover for correctional officers, the avoided cost only accounts for a fraction of the overall expense for increasing compensation. As correctional officer pay is now comparable to other state law enforcement positions and hiring is on the rise, the Alabama Department of Corrections may have to explore other methods to continue to reduce turnover and increase hiring.

Data and Methodologies

Study Design

ACES obtained employee action records from the Alabama State Personnel Department from FY15 through FY23. ACES used an interrupted time-series design to analyze the impacts of compensation changes. To do so, a date of May 29, 2019, was selected to differentiate pre- and post- program changes because it represents the earliest point as which changes to compensation could be officially communicated – when the status-quo was interrupted by treatment. The methodology created a pre-program length of 56 months and a post-program length of 52 months, providing enough time periods to perform appropriate statistical analysis of hiring and separation trends.

One of the key limitations of this design is that compensation changes occurred over a period of a few years during the post-program window. While this is a limitation of the current study, it provides an opportunity in coming years to revisit the impacts of later compensation changes.

Confounding Variables

ACES attempted to control for confounding variables by identifying data points that offered some correlation between correctional officer hiring and turnover rates. Among those with some correlation, were labor force participation rates [5] and correctional officer wages. [6]

Labor Force Participation, Hires, and Turnover Regressions

Regressions were performed to test the relationship between Alabama’s monthly labor force participation rates and the following variables:

- Correctional Officer/Correctional Officer, Senior (CO) monthly number of hires.

- CO monthly resignation turnover rates.

- CO monthly turnover rates (all types).

Hires and turnover rates were calculated by ACES. Data included in this regression spanned from FY15-FY23 (Oct. 2014-Sept. 2023), a total of 108 observations of each variable. Prior to running the regressions, outliers were removed using the interquartile range. This removed data points from April 2020 and April 2023, leaving us now with a total of 106 observations for each variable.

The regressions found:

- A moderate negative correlation (r = -0.61) between Alabama’s monthly labor force participation rate and monthly CO turnover rates from FY2015-FY2023. As labor force participation rates increase, turnover rates decrease. There is sufficient evidence to suggest that the relationship between the two variables is significant (p < 0.01).

- A moderate negative correlation (r = -0.60) between Alabama’s monthly labor force participation rate and monthly CO resignation turnover rates from FY2015-FY2023. As labor force participation rates increase, resignation turnover rates decrease. There is sufficient evidence to suggest that the relationship between the two variables is significant (p < 0.01).

- Essentially no correlation (r = 0.002) between Alabama’s monthly labor force participation rate and monthly CO hires from FY2015-FY2023.

Mean Resignation Turnover Pre/Post Program | Correctional Officer/Correctional Officer, Senior

T-tests were performed to test for a significant difference in CO monthly resignation turnover rates pre/post the program. The “Before the Program” group included monthly resignation turnover rates from October 2014 to May 2019. The “After the Program” group included monthly resignation turnover rates from June 2019 to September 2023. The data was tested for normality using the Jarque-Bera test. Though variance was determined to be roughly equal following the rule of thumb ratio, the t-tests were conducted both assuming equal variance and assuming unequal variance.

The t-tests found:

- When assuming unequal variances, the mean monthly resignation turnover rate for CO is significantly lower after the program than the mean monthly resignation turnover rate for CO before the program at a confidence level of 95% (p < 0.01).

- When assuming equal variances, the mean monthly resignation turnover rate for CO is significantly lower after the program than the mean monthly resignation turnover rate for CO before the program at a confidence level of 95% (p < 0.01).

Because there is a significant correlation between CO resignation turnover rates and Alabama’s labor force participation rate, ACES determined additional testing of rates before and after the program while controlling for labor force participation to be necessary. To achieve this, an ANCOVA test was performed using monthly resignation turnover rates and monthly labor force participation rate.

The results of the ANCOVA test found that the mean monthly resignation turnover rates before the program is significantly different from the mean monthly resignation turnover rate after the program, even when accounting for Alabama’s labor force participation rate, at a confidence level of 95% (p < .01).

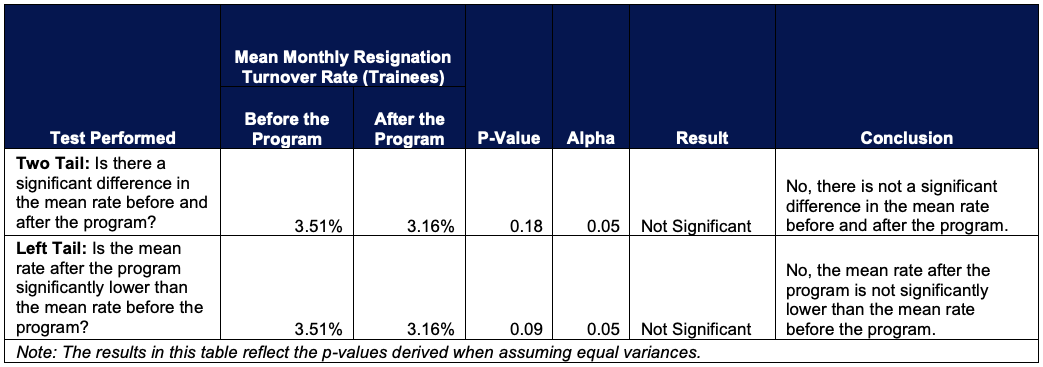

Correctional Officer Trainee

T-tests were also performed to test for a significant difference in Correctional Officer Trainee monthly resignation turnover rates before and after the program. The data was tested for normality using the Jarque-Bera test. The results of this test concluded the data was not normally distributed and therefore violated one of the assumptions of t-tests. The data was normalized using the Box-Cox method. Though variance was determined to be roughly equal following the rule of thumb ratio, the t-tests were conducted both assuming equal variance and assuming unequal variance.

The t-tests found:

- When assuming unequal variances, there is no significant difference between the mean monthly resignation turnover rate for trainees before and after the program at a confidence level of 95% (p = 0.18).

- When assuming equal variances, there is no significant difference between the mean monthly resignation turnover rate for trainees before and after the program at a confidence level of 95% (p = 0.18).

Because there was no significant difference, no further testing was deemed necessary.

Corrections Employee Wages | Mean Resignation Turnover Pre/Post Program

Regressions were performed to understand the relationship between wage increases and the number of correctional officer hires. Corrections employee’s annualized average monthly wages were analyzed both as a standalone variable and as compared to other government employees’ annualized average monthly wages from 2015 to 2022. Number of hires were analyzed in three different ways: (1) include trainees, officers, and security guards, (2) include trainees and officers, and (3) include officers only. Outliers were identified and removed using the interquartile range. (This only affected regressions ran using trainee and officer hires; 2015 was identified as an outlier and therefore excluded.)

Other exclusions included:

- All 2019 data points. The program began in 2019, and all data points are annualized. Without any real way to split the wage variable, the data point was excluded altogether.

- Regressions were later run including the 2019 data points, but it did not significantly change any of the results.

- 2018 police protection wage data was deemed to be an outlier as it was abnormally high in that year compared to all of the surrounding years ($24,000,820 in 2018 and around $5,000,000-$6,000,000 in all other years). This only affected regressions looking at the difference between police protection wages and corrections wages.

Corrections Wages as Compared to Other Government Employees

When including trainees, officers, and security guards in the number of hires variable, there is a moderate but non-significant positive correlation between the number of hires and the difference in the average wages of corrections employees and other government employees. In other words, as the average corrections employee wage got closer to or outpaced the average wage of other government employees, the number of correctional hires increased.

When including only trainee and officer hires and when including only officer hires, the correlation became stronger, but it also became negative. In other words, as the correctional employee average wage got closer to or outpaced the average wage of other government employees, the number of correctional officer and trainee hires decreased. However, this correlation is still non-significant.

Corrections Wages as a Standalone Variable

When including trainees, officers, and security guards in the number of hires variable, there is a low and non-significant positive correlation between the number of hires and corrections employee average wages. Again, this means as the average corrections employee wage increased, hires also increased.

When including only trainee and officer hires the correlation becomes stronger and negative, but it remains non-significant. However, when looking just at officer hires, there is a strong and significant negative correlation between number of hires and average officer wages—meaning as the average corrections’ employee wage increased, the number of officer and officer senior hires decreased. This is not to say that hires decreased because wages increased. The result is likely due to the way average wage was calculated for this analysis and to the creation of the security guard classification. The average wage includes all full-time corrections employees and their wages, not just officers. Additionally, when the security guard class was created, a large number of security guards were brought in while officer hires waned. This is demonstrated by the shift from a positive correlation to a negative correlation simply by removing security guard hires from the analysis while still including their wages in the wage calculation. These variables were excluded from further testing due to this explanation.